Useful Information - What is Hydrology

Key words that you will come across include: aquifer, groundwater, hydrological cycle, permeability, porosity, saturated zone, unsaturated zone, voids, water table.

Hydrogeology is the science that deals with groundwater, which has a rather mystical reputation to many people but is simply water that occurs naturally in rocks. It’s the stuff that comes out at springs, desert oases, and artesian wells in Australia, to name but a few places. Why is groundwater worth studying? One reason is that it represents a major proportion of the Earth’s usable water resources. Forget the figures you sometimes see quoted in the media, that some lake holds so many per cent of the Earth’s water; they are talking only about surface water. Of all the water on Earth, nearly 96.5% is sea water. Much of the remainder – about 2% of the total – occurs in solid form in polar ice-caps and glaciers. Virtually all of the remaining fresh water – the non-marine, unfrozen water – is groundwater. The water in rivers and lakes, in the atmosphere and in the soil, in plants and animals and you and me, together amounts to only about 1/50th of 1% of the world’s total water supply. A second reason is that in some areas groundwater is the only source of water and in many others it is the most economical and environmentally acceptable source. A third reason is that despite being essential to life in many parts of the world, groundwater – like surface water in times of flood – can sometimes be a nuisance or even a danger – when digging a quarry or mine, for example.

How does groundwater occur?

Nearly all rocks in the upper part of the Earth’s crust, whatever their type, age or origin, contain openings called pores or voids. These voids come in all shapes and sizes. Some of them are too small to be seen with the unaided eye. Exceptionally, at the other end of the scale, limestone caverns may be tens or hundreds of metres across.

One common rock, sandstone, has pores that are easily visualised. If you take a handful of sand and look at it closely – preferably through a magnifying glass – you will see that there are numerous tiny openings between the grains of sand. (If you cannot readily find a handful of sand, look at granulated sugar which shows exactly the same feature.) Sandstone is merely sand that has turned into rock because the grains of sand have become cemented together, and most of the openings will usually have been retained in the process – it is as though our granulated sugar had become a block of sugar.

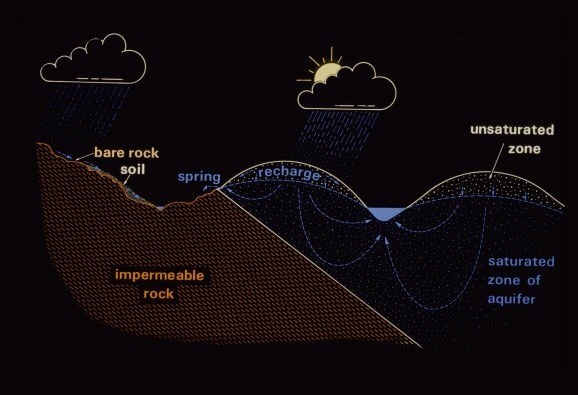

The property of a rock of possessing pores or voids is called porosity. Rocks containing a relatively large proportion of void space are described as ‘porous’ or said to possess ‘high porosity’. Soil also is porous. On a hot summer day the surface soil may appear quite dry, but if we dig down a little way the soil feels damp; if we can dig far enough to reach rock, this too will feel damp. The reason for this is that the pores are not all empty; some of them are filled, or partly filled, with water. In general it is the smaller pores that are full and the larger ones that are almost empty. At a still greater depth we should find that all the pores are completely filled with water, and we should describe the rock or soil as ‘saturated’. In scientific terms we should have passed from the unsaturated zone to the saturated zone.

If we dig or drill a hole from the ground surface down into the saturated zone, water will flow from the rock into our hole until the water reaches a constant level. This will usually be at about the level below which all the pores in the rock are completely filled with water – in other words, the top of the saturated zone. We call this level the water table. Notice that the water table is a surface that separates the unsaturated and saturated zones – it is wrong to use it to describe the body of groundwater.

The distance we need to drill or dig to reach the water table varies from place to place; it may be less than a metre, or more than a hundred metres. In general the water table is not flat; it rises and falls with the ground surface but in a subdued way, so that it is deeper beneath hills and shallower beneath valleys. It may even coincide with the ground surface. If it does we can easily tell, because the ground will be wet and marshy or there will be a pond, spring or river. Where the water table is below the ground, as is usual, its depth can be measured in a well or borehole.

All water that occurs naturally below the Earth’s surface is called sub-surface water, whether it occurs in the saturated or unsaturated zones. Water in the saturated zone (below the water table) is called groundwater. This water usually takes part in the hydrological cycle, though its residence time in the ground may range from less than a day in some limestone areas to centuries, millennia or longer in large arid basins.

Aquifers

Virtually all rocks contain some groundwater. How much water they contain, how easily it can flow through them and how useful they are as sources of water depends largely on three factors.

The first is the porosity – if there are no voids, then clearly the rock cannot contain water.

The second factor is a combination of the size of the pores and the degree to which the pores are interconnected, because this combination will control the ease with which water can flow through the rock. We call this factor the permeability. Materials that allow water to pass through them easily are said to be permeable; those that permit water to pass only with difficulty, or not at all, are poorly permeable or impermeable. A rock may be porous but relatively impermeable, either because the pores are not connected or because the pores or the connections between them are so small that water can be forced through them only with difficulty. Conversely, a rock that has no voids except for one or two open cracks will have a low porosity, and will be a poor store of water, but because water will be able to pass easily through the cracks the permeability will be high. Layers of rock sufficiently porous to store water and permeable enough to allow water to flow through them in useful quantities are called aquifers; the word comes from Latin and means ‘water carrier’.

The third factor that determines the amount of groundwater available from the rocks of an area is the amount of replenishment – the degree to which water abstracted from the aquifer is replaced. This replenishment may come from adjacent aquifers but usually comes from above, as a result of rainfall soaking into the ground.

The replenishment factor depends not only on the nature of the rocks but on the soil and vegetation that cover them and on the climate of the region. It is part of the water balance of the area – the balance between the water that enters the area and the water that is used or that leaves it. In assessing the groundwater resources of any region, knowledge of the water balance is as vital as knowledge of the porosity and permeability of the rocks. This is because groundwater is not isolated from other water but is part of the Earth’s total store of water. As such, it is in more or less continuous interchange with all other water in a system of circulation called the hydrological cycle.

Groundwater plays a vital role in the hydrological cycle by providing storage. In areas underlain by impermeable rock, rainfall cannot penetrate far below the soil – it flows through or – very occasionally – over the soil to surface streams, which rise quickly after heavy rainfall and may flood. When the rain stops, the flow to and in the streams quickly decreases. This leads to streams and rivers that are termed ‘flashy’. Where the underlying rock forms an aquifer, rainfall can soak in and down through the rock to the water table, causing it to rise. Where the water table reaches the ground surface (usually in a valley) groundwater leaves the aquifer and contributes to the flow of the stream. This process occurs much more slowly than the flow over impermeable ground, so the water is held in storage and released slowly; this means that rivers sustained by groundwater (known as gaining streams) keep flowing when there is no rainfall.

In Britain, we often say that roughly a third of public water supplies come from groundwater (a lower figure, incidentally, than for most countries in Europe) but this takes account only of water drawn directly from wells. About another third of our water is drawn from rivers and most of those rivers keep flowing in dry weather only because they are sustained by groundwater.

All rainfall is really trying to become groundwater; gravity is trying to send it down into the ground. It only becomes surface water if the ground is impermeable or frozen, or because the storage space is already full, so that the groundwater flows out from an aquifer. I sometimes have to remind my colleagues who deal with rivers, lakes and the like of an important if unwelcome fact – their surface water is just the water that the ground has rejected!

For more information see Introducing groundwater (second edition, 1996, Routledge) from which much of this section is condensed, or go to the web site of the US Geological Survey, starting at http://ga.water.usgs.gov/edu/earthwherewater.html